The Sources of Old English and Anglo-Latin Literary Culture, 500-1100 (SOEALLC, formerly Sources of Anglo-Saxon Literary Culture, or SASLC) is a longstanding endeavor to create a comprehensive bibliographic resource about all authors and works known in England between c. 500 CE and c. 1100 CE. Begun in 1983 as the result of an international symposium on the use of sources in works from early England, the project is fundamentally a scholarly resource that provides basic encyclopedic information about works and manuscripts that circulated in England to c. 1100.

Major overarching objectives of SOEALLC include: 1) commissioning, editing, and publishing scholarly entries about authors and works known in early England; 2) implementing open-access online publication of all finished entries as a public resource; and 3) creating a database of searchable and usable data gleaned from entries completed by contributors. Entries bundled together into print volumes will be published with Amsterdam University Press, while other entries and the database will be published online via Humanities Commons.

Because the primary audience of SOEALLC is interdisciplinary medievalists, the project also provides comprehensive bibliographies of relevant scholarship in the fields of literary studies, religious studies, history, and art history, which must be regularly updated to reflect new publications. Ongoing SOEALLC work includes locating new articles and editions, compiling new entries and bibliographies, and editing contributions for online publication. In addition to this, we are also in the process of creating an online platform to facilitate publication of all finished entries of the project, with a database of searchable and usable data from entries already completed by contributors.

In 2019, the editorial board decided to change the name of this project from Sources of Anglo-Saxon Literary Culture (SASLC) to Sources of Old English and Anglo-Latin Literary Culture, 500-1100 (SOEALLC). We hope that this new name preserves the spirit of the project’s focus on tracing the literary sources used by authors in England during this period. At the same time, the editorial board feels that this new name more accurately represents the body of literature researched in this project and current historicized understandings of the field. In making this change, the editorial board would like to thank the scholars responsible for founding the project in the 1980s as well as BIPOC colleagues in the field who have recently worked to demonstrate the historically problematic nature of the term “Anglo-Saxon.” In this spirit, the editorial board of SOEALLC promotes the values of equity, diversity, and inclusion for all those who research the various aspects of early England.

A Sample SOEALLC Entry

The founders of SOEALLC composed this document to help readers understand the different components of a SOEALLC entry. It will be helpful to supply a more detailed breakdown for non-specialists, coupled with a visual aid.

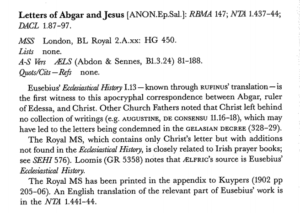

Above is a complete sample SOEALLC entry (albeit, a short one). This entry is for a biblical apocryphon commonly known as the Letters of Abgar and Jesus. The first information you encounter is called the headnote, containing various summary data and resources. Next to the bolded common title is the short title [ANON.Ep.Sal.] (which is based on Michael Lapidge’s short titles for the project), followed by abbreviations for standard scholarly reference works that are most commonly used by scholars (RBMA = Repertorium Biblicum Medii Aevi, etc.). Abbreviations are perhaps one of the most disorienting things for readers who are new to SOEALLC–there are lots of them and they are everywhere. Many of the abbreviations in the entries may be found in the list of standard Reference Works and Abbreviations for the project.

After the title line is a list of manuscript versions of the work that were written or owned in England up to c. 1100 (MSS, which is the standard abbreviation for “manuscripts”; MS is singular “manuscript”). The manuscripts are listed by their shelfmarks, which designate the library in which the manuscript is housed (in this case, the BL, or British Library, in London) plus a series of titles and numbers that designate the specific collection and “shelf” on which the MS is or was originally kept (Royal 2.A.xx). This webpage from the British Library explains shelfmarks in some detail, with the famous Cotton Collection as the example. This is actually one of the categories of information that may have changed since an entry was initially completed. Scholars are always discovering new source connections, but they also occasionally discover new manuscript attestations of a work known in early England. It is very important that SOEALLC entries remain up to date with all manuscript and standard edition information. Libraries sometimes also change the shelfmarks of their manuscripts, and even the names of the libraries themselves, so we need to take account of those changes.

MSS is followed by Lists, which refers to booklists that may record the existence of the work in a given library or scriptorium, but which don’t preserve full copies of the work. These references are all based on an article by Michael Lapidge (abbreviated ML, see Reference Works and Abbreviations), including all of the known, surviving booklists from early England.

OE Vers refers to versions of the work that are translated into Old English. In this case, a version of the Letters appears in Ælfric’s Lives of Saints (abbreviated ÆLS). The ÆLS abbreviation comes from the short title designated by the Dictionary of Old English for OE works (see the DOE’s searchable list of texts with more information about titles, abbreviations, and editions here). Also listed with A-S Vers is what is known as a work’s Cameron number (in this case, B1.3.24), a standard reference system for Old English works.

Finally, there is Quots/Cits and Refs, which are short for “quotations/citations” and “references.” These are basically what they sound like: a quotation is a direct use of the language of the work (e.g. “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit”); a citation is both a quotation and an authorial name and/or work title together (e.g. As Tolkien said, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit”); and a reference (like an allusion) is a note about a work’s author or title without direct quotation (e.g. Tolkien wrote about hobbits in his groundbreaking novel The Hobbit). In other SOEALLC entries, these lists might be very long, if the work was cited by other authors extensively. When quotations or citations are itemized, reference is given first to the passage in the source text that is being quoted or cited, followed after a colon by a reference to the passage in the Old English or Anglo-Latin text that quotes or cites it (references in both cases are to the standard critical editions; for details on the format, see the Guide for Readers). A source text, of course, can itself be an Old English or Anglo-Latin one. Note that sometimes in the headnote you will find a piece of data accompanied by a question mark (“?”), which means that there is some reason to question the force of evidence in scholarly claims about that data; these are usually discussed in the following section of the entry (the body).

Following the headnote, there is a discussion of any other historical or scholarly information that seems relevant. Our rule of thumb in composing these discussions is to ask ourselves–if a scholar consults a SOEALLC entry while they’re doing research on a work, what would they want to know about how the work circulated in A-S England that isn’t already clear from the headnote? These discussions are called the body of the entry. The main purpose of the body of the entry is to discuss the history of scholarship (called historiography) about the evidence summarized in the headnote: in other words, what scholars have discussed and argued over the years in order to make the case for knowledge of a specific work in early England. The bodies of entries can also be quite long. Sometimes, the discussion for a given author can be as long as a book, and several SOEALLC entries have been published this way.